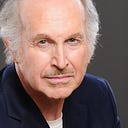

REMEMBERING AN UNEXPECTEDLY LONG, CANDID CONVERSATION WITH THE GOLDEN AGE STAR OF STARS

(I had one of the last interviews with Cary Grant. When he died of a stroke at the age of 82 on November 29, 1986, I was asked to write an appreciation for my newspaper and its wire service. This is the core article, with updates.)

“Cary Grant is the only actor I ever loved in my whole life.” ~Alfred Hitchcock

By Gregory N. Joseph

IT WAS, CARY GRANT was saying, “the more gracious period” — that time spanning his first film in 1932 (“This Is the Night”) and his 72nd and last in 1966 (“Walk, Don’t Run”).

He didn’t add — but might have, had he been moved to abandon his patented air of unruffled civility — that his final year in the movies not so coincidentally also marked the moment when Hollywood’s taste, its sly gift for understatement and sexy innuendo, hallmarks of the unerring Grant style, metamorphosed forever with the taboo-shattering “adult” movie, “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?”.

He might have said, “How could Cary Grant do any of that rubbish?” He might have recalled, as did I, that Sunday night in June of 1971 when he and his “To Catch a Thief” co-star Princess Grace of Monaco (known in her Hollywood days as Grace Kelly) blew the hot screen couple of the millisecond, Ryan O’Neal and Ali McGraw of “Love Story,” off the stage in a star-studded yesterday-meets-today tribute to the “retiring” Frank Sinatra at the Los Angeles Music Center (the mercurial Sinatra, a friend of Grant’s, came out of retirement a few short years later).

He might have done either of those things. But he did not. (He certainly would have had every right: A 1987 People magazine poll chose him as the greatest movie star of all time; in 1999, the American Film Institute ranked him second only to Humphrey Bogart on its “American screen legend” list of male actors, which honors actors recognized for their contributions to classical Hollywood cinema — “an actor or team of actors with a significant presence in American feature-length films whose screen debut occurred in or before 1950, or whose debut occurred after 1950 but whose death has marked a complete body of work.”)

Instead, Grant, at his home in Beverly Hills, munched half of a “wonderfully delicious English muffin” delivered by his young wife, Barbara, and analyzed the bright Technicolor and murky Kafkaesque elements of his life with equal aplomb.

Our interview was to serve as an advance of his appearance in San Diego for “A Conversation with Cary Grant,” the same traveling question-and-answer retrospective of his career the 82-year-old actor was scheduled to deliver soon thereafter in Davenport, Iowa, when he suffered a massive stroke and died.

Our 10 a.m. chat was supposed to be, according to a press representative, relatively brief and somewhat well-scripted. But that was not who Cary Grant was.

In fact, it evolved into a long, wide-ranging conversation that would last several hours and be terminated not by him, but — to my everlasting sorrow — by me, because I had to get back to work.

During our discussion, he spoke of his transformation into a film star, of his shoulder-dipping American-cum-cockney way with romantic comedy, of directors and roles he liked (and disliked), of criticism that he wasn’t so much acting as playing himself, of glimmers of the real Cary Grant audiences might spy in his old films.

“You don’t lose your own identity up on the screen.” he was explaining with graceful force. “It’s always you, no matter how you behave.

“How can you lose your own identity, because you’re there, in the flesh, photographed and blown up? How the hell can you lose yourself — what do they mean, lose yourself? You mean you feel hypnotized?

“It’s rather stupid for critics to knock Gary Cooper or Duke Wayne for playing themselves, because they were both number one at the box office for many years. It’s much more difficult than anyone could possibly imagine.”

Grant — born Archibald Alec Leach into an impoverished family in Bristol, England — may have looked wonderful in tails and symbolized every faithful movie fan’s notion of elegance, but one had to believe this was either a happy accident or a carefully crafted creation. It apparently was not the real Cary Grant, or at least as he fancied himself.

For that, he said the picture that revealed the most accurate glimpse of him was “Father Goose”: “That suited me just fine. I had to wear one shirt and one pair of pants and not shave, and that was great. It wasn’t the most successful film by any means, but a very happy occasion for me.”

And Grant also spoke of the not-so-happy occasions — of rumors of his homosexuality, of charges he took LSD, and of the gritty, gossipy 1983 biography “Haunted Idol” by Geoffrey Wansell, which not only delved into those questions but also his alleged miserliness and four broken marriages (the last divorce, from actress Dyan Cannon, was a messy, potentially image-puncturing affair).

When those subjects were broached, there were flashes of an anger the public had never beheld, a deeper wounding than the camera could ever disclose. It was not a pleasant direction. Yet Grant himself led the way, doing so professionally, with the sort of steel-sheathed directness that no doubt propelled his career, a side of him in absolute contrast to the easygoing playboy whose only answer to such charges on the screen would have been a piercing glance.

Grant, while never forsaking the gentility he spent a lifetime learning and mastering, didn’t flinch as he turned the guns back on those who claimed he was a homosexual. He said the rumor started because some men were jealous of his movie persona and seized on the subject to counteract their girlfriends’ interest in him, and that the smear was reinforced by a vengeful gossip columnist of the day (he didn’t name the person, but it was Hedda Hopper, a loathed and feared figure in Hollywood whose readership reached 35 million people at the height of her power in the 1940s; she continued to produce her column until her death in 1966 at the age of 80).

“You don’t fight those rumors,” he said. “You let it be what it is. Who cares? The hell with it. What difference would it make if I was, anyway?”

As for the LSD, he said that, yes, he had taken the drug “as a method of being happier” in a group under a doctor’s care years ago. If he suffered depression — another thing he might have said — it was understandable.

Here was a man whose mother was placed in a mental institution when he was 9; he didn’t see her for two decades.

Grant did little to mask his contempt for the unauthorized biography about him, or similar books about fellow stars of Hollywood’s halcyon days.

The famous voice that had shaken scores of 1940s movie palaces in films like “His Girl Friday” and “Arsenic and Old Lace” was now rattling our conversation.

“This man (Wansell) wrote, ‘Cary Grant was thinking about this as he was driving … “ Now, how the hell does he know what I’m thinking?” he asked of the author, his voice rising.

But the actor’s mood soon mellowed and he wondered if I was going to be on hand for his upcoming appearance in San Diego. He asked my wife and I to join him and his Barbara backstage after the show.

When I told him that I could not do so because of scheduled back surgery, he said he had suffered from a similar ailment 40 years before. “Are you in pain?” he asked. “Are you going to let them do that to you?”

He went on, pleading in a gentle, avuncular way, this movie star of movie stars, suggesting I reconsider having the operation. “How old are you?” he went on. “Well, I was the same age with the same symptoms you describe, and the studio sent me to a chiropractor. Now I’m not espousing chiropractors, mind you, but for me it worked. You should really consider that.”

I thought out loud that perhaps it would not be his only program in San Diego. He might be back again, and perhaps we could touch base then.

Almost in little-boy fashion, Grant confided that he had led a Garbo-like seclusion for many years — for the simplest of reasons, one with which many people can relate.

“I dread making a speech,” he said, his voice dropping. “I haven’t the confidence to believe that I’m holding the audience’s attention.”

Ah, but hold our attention he did.

When he died, The New York Times stated in an editorial: “Cary Grant was not supposed to die … Cary Grant was supposed to stick around, our perpetual touchstone of charm and elegance and romance and youth.”

Now, all these years after his passing, it’s clear that Cary Grant has never really left us, not in all the important ways. Audiences still want it that way.