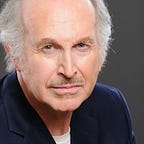

The Golden Age Star of Stars Talks About His Image, Rumors and the Hard Work of Making It All Look Easy

“Some actors squeeze a line to death. Cary tickles it into life.” — Michael Curtiz, director (“Night and Day,” “Casablanca”)

“Cary Grant is the only actor I ever loved in my whole life.” — Alfred Hitchcock, director (“Suspicion,” “Notorious,” “To Catch a Thief,” “North by Northwest”)

“Cary Grant never won an Oscar, primarily, I suspect, because he made everything look so effortless. Why reward someone for having fun, for being charming?”— Richard Russo, novelist and screenwriter (“Empire Falls,” “Nobody’s Fool”)

By Gregory N. Joseph

CARY GRANT WAS EXPLAINING, openly, graciously and without bitterness, the ups and downs of his life and career. It was a wonderful, yet bittersweet moment: one of the last interviews Cary Grant would ever give.

A fascinating, revealing, hours-long conversation in which he analyzed the bright Technicolor and murky Kafkaesque elements of show business with equal candor.

Born Archibald Alexander Leach on Jan. 18, 1904, in Bristol, England, he would die shortly after our chat, on Nov. 29, 1986, suffering a massive stroke in Davenport, Iowa, where he had gone to appear in another leg of his national stage tour, “Conversation with Cary Grant.”

He thought about death often when I spoke to him, the man that a 1987 People magazine poll chose as the greatest movie star of all time. (In 1999, the American Film Institute ranked him second only to Humphrey Bogart on its “American screen legend” list of male actors, which honors actors recognized for their contributions to classical Hollywood cinema — “an actor or team of actors with a significant presence in American feature-length films whose screen debut occurred in or before 1950, or whose debut occurred after 1950 but whose death has marked a complete body of work.”)

“Do you ever wonder how it will happen?” he asked, referring to death. “Do you wonder whether you will embarrass yourself?”

Cary Grant didn’t embarrass himself at his demise (he simply said “I’m sorry” to his young wife, Barbara), nor did he ever in life.

His 72nd film, 1966’s “Walk, Don’t Run,” would be his last. By choice.

In our discussion on April 4, 1985, Grant explained his reclusiveness, second only to Grabo’s, had come about: “Yes, I’ll tell you really why. I dread making a speech. I haven’t the confidence to believe that I’m holding the audience’s attention.”

Yes, Grant admitted, he realized he seemed to be playing himself on the screen: “Who the hell doesn’t?”

But he explained his screen persona wasn’t the real Cary Grant. The closest screen role to the real him, he said, was the tattered, charming grump in “Father Goose,” not the suave guy with the square jaw, cleft chin, raven slick-backed hair, glittering brown eyes and lean, athletic build.

This was a man, according to Michael Curtiz, who directed Grant in the loosely-based biography of composer Cole Porter, “Night and Day,” unlike nearly any other actor: “Some actors squeeze a line to death — Cary tickles it to life.”

Explained Grant: “It’s very difficult for people to be yourselves at any time. You can walk into a party and not necessarily be yourself. You want to create an illusion or create a man that you possibly are not — or a woman, certainly some women I know go through some very difficult times, and I’ve always felt very sorry for them, not being able to be themselves.

“You don’t lose your own identity up on the screen. It’s always you, no matter how you behave. How can you lose your own identity, because you’re there, in the flesh, photographed and blown up. How the hell can you lose yourself? What do they mean? You mean you feel hypnotized?

“It’s rather stupid for critics to knock Gary Cooper or Duke Wayne for playing themselves, because they were both number one in the business for many years. It’s much more difficult than anyone could possibly imagine. None of this comes naturally, it’s from experience that takes practice.

“Just as a writer says he improves from year to year — you look at some of your old stuff and say, ‘My God!’ — well, so does an actor. You have to have ambition, which puts you at that next step.”

Grant said he seldom watched his old movies.

“When I do,” he confided, “I always know, from duly acquired knowledge, that I could have done this or that better, and perhaps, so could the director.”

The influential and often bruisingly contentious film critic Pauline Kael, in a long profile of him in the July 14, 1975, New Yorker magazine, summed him up this way:

“Cary Grant’s bravado — his wonderful sense of pleasure in performance, which we respond to and share in — is a pride in craft. His confident timing is linked to a sense of movies as popular entertainment: he wants to please the public. He became a ‘polished,’ ‘finished’ performer in a tradition that has long since atrophied. The suave, accomplished actors were usually poor boys who went into a trade and trained themselves to become perfect gentlemen. They’re the ones who seem to have ‘class.’ Cary Grant achieved Mrs. Leach’s ideal, and it turned out to be the whole world’s ideal.”

The movie star of movie stars left life’s stage as quietly as he could.

When Cary Grant died, there were no services. He was cremated and the ashes returned to his family for private dissemination, in accordance with his final wishes.

Perhaps that shouldn’t have come as any surprise at all for the man who once observed: “Everybody wants to be Cary Grant. Even I want to be Cary Grant. I have spent the greater part of my life fluctuating between Archie Leach and Cary Grant; unsure of either, suspecting each.”

It was left to the rest of us to be sure. We were, and still are.

In what is considered one of the greatest slights in Academy Award history, Cary Grant never received an Oscar for his acting (he was nominated only twice, for 1941’s “Penny Serenade” and 1944’s “None But the Lonely Heart,” losing both times). The Academy did its best to right that wrong on April 7, 1970, when he was presented with an Honorary Oscar at the 42nd Academy Awards during televised ceremonies at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in Los Angeles. Presented to him by his friend Frank Sinatra, the award was bestowed upon Grant “for his unique mastery of the art of screen acting, with the respect and affection of his colleagues.”

Here’s what he said in accepting the honor:

“I think you’re applauding my stamina.

“I’m very grateful to the Academy’s Board of Directors for this happy tribute and to Frank for coming here especially to give it to me. And well, to all the fellows who worked so hard in finding those and assembling those film clips.

“You know, I may never look at this without remembering the quiet patience of the directors who were so kind to me, who were kind enough to put up with me more than once, some of them even three or four times. There was Howard Hawks, Hitchcock, the late Leo McCarey, George Stevens, George Cukor and Stanley Donen. And all the writers. There was Philip Barry, Dore Schary, Bob Sherwood, Ben Hecht, dear Clifford Odets, Sidney Sheldon, and more recently Stanley Shapiro and Peter Stone. Well, I trust they, and all the other directors, writers and producers and leading women, have all forgiven me what I didn’t know.

“I realize it’s conventional and usual to praise one’s fellow workers on these occasions, but why not?! Ours is a collaborative medium, we all need each other. That’s how we exist. And what better opportunity is there to publicly express one’s appreciation and admiration and affection for all those who contribute so much to each of our welfare. You know, I’ve never been a joiner or a member of any particular social set, but I’ve been privileged to be a part of Hollywood’s most glorious era. And yet tonight, thinking of all the empty screens that are waiting to be filled with marvelous images and idealogies, points of view, whatever, and considering all the students who are studying film techniques in the universities throughout the world and the astonishing young talents that are coming up in our midst, I think there’s an even more glorious era right around the corner.

“So, before I leave you, I want to thank you very much for signifying your approval with this. I shall cherish it until I die, because probably no greater honor can come to any man than the respect of his colleagues. Thank you. So long.”