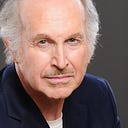

CONVERSATION WITH ‘STAR TREK’ CREATOR GENE RODDENBERRY: How He Arrived at a Classic — and What He Refused to Do

By Gregory N. Joseph

GENE RODDENBERRY died at a relatively young but malady-plagued 70 years of age on Oct. 24, 1991, but he nonetheless lived long enough to witness his “Star Trek” creation evolve from a cult TV and movie franchise into an influential cultural phenomenon that, if anything, seems to gain momentum — and followers — by the year.

This would have come as a shock to anyone scanning the TV ratings when the original series made its debut. So unsure of the show and confused by what it had was NBC that it bounced the program around from Thursdays to Fridays to Tuesdays facing a plethora of competition over three short years before finally ignominiously canceling it.

But in some ways, one can almost excuse the network, whose decision-making back then was largely governed by the numbers. Indeed, the long-forgotten (and justifiably so) “Mr. Terrific” and “Iron Horse” were just two of the series placing ahead of “Star Trek” in the 1966–67 season, the show’s first year on television — and its best year during its inaugural network run. Not exactly reassuring results for those paid to figure out a middle ground of popular viewing tastes for those at home.

But maybe that was the problem.

In historic show business terms, it remains perhaps the quintessential example of how wrong measuring popular heft can be while missing that an outside-the-box concept takes time to build wide appeal.

By November of 1982, when I spoke to Roddenberry, “Star Trek” was cemented in the science fiction firmament, playing endlessly in reruns on TV (there were 79 original episodes), and amplified by television spinoffs and various versions on the big screen. It’s safe to say that if NBC could have (accurately) looked into the future, it might have chosen to do things differently.

By the time of our conversation, to mix a science fiction metaphor, the force was with Roddenberry as Hollywood began beaming down the likes of sci-fi hits like “2001: A Space Odyssey,” “Star Wars,” “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” and “E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial” — projects that one could strongly argue Roddenberry had laid the ground work for.

But it wasn’t easy.

Roddenberry, like his greatest creation, came to fame the hard way.

A native of El Paso, Texas, he transferred from pre-law to engineering in college, then dropped out to enlist in the Army Air Corps in World War II. He was sent to Guadalcanal, where he flew B-17s in 89 missions and sorties, and began writing while in the South Pacific.

After the war, he went to Pan Am as a commercial pilot, then in 1949 joined the Los Angeles Police Department, where his father had served, spending about the first year and a half in the traffic division before joining the public information section, then becoming the police chief’s speech writer. He became a technical adviser for early-TV Los Angeles-based cop shows like “Mr. District Attorney,” at one point writing scripts for the series under the pseudonym “Robert Wesley.” That led to other television assignments that finally convinced him to resign from the police department in 1956 to concentrate on his writing.

“I wasn’t like Joe Wambaugh,” Roddenberry told me, referring to the cop-turned-author of such best sellers as “The New Centurions” and “The Onion Field.” “Joe was a career cop. I got in because I wanted to be a writer, and get to know about life.”

Eventually, Roddenberry became the head writer for one of early-TV’s most popular “adult Westerns,” “Have Gun, Will Travel,” about a cultured, black-clad gunfighting Old West “knight” of conscience played by Richard Boone who hired out in a quest for justice. Roddenberry then went on to create the short-lived but critically acclaimed “The Lieutenant” TV series, ironically starring future “2001” co-star Gary Lockwood as an idealistic young Marine. “Star Trek” soon followed.

The common denominator of Roddenberry’s projects was becoming apparent: the heroic pursuit of bettering mankind against great odds. And, uniquely for the time, peaceful solutions were preferred.

“If I were making the ‘Star Trek’ series again,” he confided, “I’d like to get into what’s happening in orbital space, and the amazing technology. Oh, I might touch on some social issues, I don’t know. These are different times. The ‘Star Trek’ series was the first to really come out against the Vietnam War — did you know that?

“What sets it apart from other science fiction show, I think, and what appeals to people, is that we focused on the united brotherhood of living beings — tolerance. That’s a powerful statement.

“And we didn’t deal with anti-heroes — we went for the old-fashioned kind. And we weren’t like ‘Battlestar Galactica,’ which always has to do with a fighting future. People don’t want to hear that.”

Roddenberry didn’t consider himself a science fiction writer. His ideas stemmed from then-current issues framed in a positive way.

“I don’t have a scientific mind,” he said. “Some people have good pitch. I just grew up with a certain ability to see how things might be going and make good guesses as to where they would end, that’s all. That’s what I would try to do again.”

He and others involved in making the original “Star Trek” paid an enormous personal price, he said.

“Those were 12-hour days, six days a week,” he sighed. “I had children growing up I couldn’t give the proper time to, time that they deserved.

“There were three divorces among people at our office at the studio, and there wasn’t one of us who didn’t, at one time or another, wind up in the hospital for exhaustion.”

In November 1991, shortly after Roddenberry died, I spoke with William Shatner, the first “Star Trek’” Capt. James T. Kirk. By then, of course, “Star Trek” had taken off as a solid cult classic.

“I never watch the old series,” Shatner said. “It’s like looking at old pictures of yourself, you know what I mean? I just don’t like to do it.”

He may not, but scores of others still do — in sequels, spinoffs and unlikely manifestations that few could have imagined more than a half-century ago. Even Gene Roddenberry might be surprised at how his old series has gone where few have gone before.