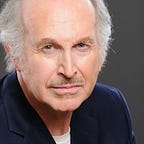

One of Hollywood’s Greatest Cinematographers — and Paradoxes

(Haskell Wexler [1922–2015] was named one of the 10 most influential cinematographers in film history by the International Cinematographers Guild, his works including “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?”, “In the Heat of the Night,” “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” “American Graffiti,” “Bound for Glory,” “Days of Heaven,” and “Medium Cool” [which he also directed]. Six of his films have been preserved by the National Film Registry, and George Lucas has established the Haskell Wexler Endowed Chair in Documentary at the USC School of Cinematic Arts. As a profile subject he was as complex, and fascinating, as they come. First published in March 1982.)

By Gregory N. Joseph

“TRY NOT TO MAKE TOO BIG a thing out of my once being a Communist,” Academy Award-winning cinematographer Haskell Wexler — a paradox who has called both Jane Fonda and John Wayne close friends, photographing her in “Coming Home” and him in Great Western TV commercials — was saying before he got up to change his shirt.

“I’m not sure a lot of people would understand.”

Probably not, unless they had the benefit of both surveying Wexler’s cinematography — in such films as “The Best Man,” “America, America,” “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” and “Bound for Glory” (the latter two for Oscars) — and perhaps sitting down for a few hours to listen to him agonize over why he has always done what he has done, politically or otherwise.

And maybe not even then, since Wexler — who has become something of a symbol of leftism in Hollywood over the last 30 years — only seems to know what he has to do, rather than exactly why.

What is certain is that he tends to express his views cinematically, whether running them through a camera on film, or speaking them out loud.

Film — the language thereof — is his Webster’s Collegiate, as became apparent during an interview prior to his appearance at the San Diego Museum of Art for the third installment of the “Hollywood Film: The Collaborative Art” lecture series there.

“I guess if I were to give a reason for what I do,” Wexler said, sliding back down in a stuffed armchair and resting his foot on a nearby desktop, “I’d have to look at Tom Joad’s speech at the end of ‘Grapes of Wrath.’

“I like what he said. He said something to the effect that people who have the privilege of reproducing ideas so that many more people can see those ideas have the responsibility to people of less privilege of helping make the world a better place. I know that sounds corny, but that’s what I believe in.

“Lots of films today just seem to say, ‘Me, me, me,’ about the filmmaker, they don’t carry out that responsibility.”

Wexler, a Chicago-born, 60-year-old whippet of a man given to dressing in work shirts, corduroy pants and suede jogging shoes, is most comfortable squinting through the eyepiece of a camera, any camera, cradling it as he would a third arm while sizing up the photographic possibilities of a scene.

An hour or so before our meeting, he had been pacing the stage at the Museum of Art’s Copley Auditorium with a videotape camera slung casually over his shoulder, running a small group of drama students from Grossmont College through a rehearsal of a cutting from “The Importance of Being Earnest.” Later that night, during his talk on cinematography, he planned to shoot the sketch for real and play it back to his audience to demonstrate the difference between viewing a stage play and cinema verite.

The talk was to follow a screening of the film “Days of Heaven,” which won Nestor Almendros a 1978 Oscar for cinematography, despite the fact Wexler had shot half of it (and received credit only for “additional photography”).

“Nestor’s a friend of mine,” Wexler explained during the ride back to the hotel following the rehearsal. “We talked about that (the Oscar) and I decided I already had won it twice, and the photographic concept was his, so he should have the award. I did it his way, anyway. I can’t say I agree with him all the time. He has this thing about natural lighting, and I think it’s full of (bleep). I mean film is an unnatural thing, you have to create things, they just don’t happen — oh, hell, I’ll get into that back up in my room.”

And he did, carefully explaining, as though leading a graduate seminar in cinematography, why natural lighting in a commercial film was really never natural, but carefully planned. If it weren’t, he said — using the light that filtered through his hotel room window for illustration — millions of dollars would be spent on additional shooting time and good performances often would be lost because of frustrated actors who would have to start reshooting scenes from the middle. “If you had to break and wait for natural light,” he allowed, “nothing would ever get made.”

Probably his easiest film to shoot, he said, was “American Graffiti,” because “the way we did it was as loose as the subject matter.” The most difficult, he added, was the 1973 documentary he produced and directed, “Brazil Report of Torture.”

“The ‘Brazil Report’ was the first time there had been documented proof that a Latin American country was torturing people,” he said. “It was run in the United Nations and Sen. Ted Kennedy brought it up in the Senate in his efforts to try to minimize aid to the government there.

“I had been in Chile filming just before that, hadn’t really planned on doing it, and I went down with no crew except two Chilean guys. The reason I say it was most difficult for me to do is because both of those guys ended up getting killed later over it.”

Another difficult picture to do, he said, was the 1974 documentary about North and South Vietnam, “Introduction to the Enemy,” which he made with his friends Jane Fonda and her husband, Tom Hayden (“Anyone who has or is concerned with the war should see it,” wrote The New York Times, “along with those who think the war is over.”)

“In many ways I felt voyeuristic doing the film,” he said, his voice trembling slightly. “There was a guy killed by a land mine as we were shooting, and I followed him from the time of the explosion to the time he died.

“I had to quickly evaluate whether to keep filming or to try to help keep this man from dying, to figure whether I could have done any good or whether the film would do more good in the long run. Sometimes I feel like I should put the goddam camera down and help — it’s a decision I’ve had to make a lot of times.”

He said he faced a similar dilemma on yet another controversial documentary, the 1976 film, “Underground,” a clandestinely shot movie in which Weather Underground members told how they bombed the U.S. Capitol and other targets. The film was produced by documentarist Emile de Antonio (who had also made critical documentaries on former President Richard M. Nixon and the late Sen. Joseph McCarthy) and released at a time when its chief characters were the objects of a national search by the FBI.

As a result, the U.S. Attorney’s Office issued federal subpoenas for Wexler and other involved in the film project (including the cinematographer’s son, Jeff, a motion picture soundman). The subpoenas were mysteriously withdrawn, because, Wexler contends of pressure brought to bear by “anybody who was anybody in Hollywood, from Barbra Streisand to Jack Nicholson” (Wexler photographed “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” for which Nicholson won the 1975 best actor Oscar).

All five Weatherpeople who starred in the film — Bernardine Dohrn, Billy Ayers, Kathy Boudin, Cathy Wilkerson and Jeff Jones — were subsequently arrested.

“I knew where these people stood before they went underground,” Wexler said. “I also knew they had taken credit for certain violent acts … but I was interested, I guess you could say, because it was a source of adventure to pursue.

“I didn’t believe and I don’t believe that violence accomplishes anything, in the United States of America or anywhere else in the world. I believe there are enough avenues, in this country especially, for expressing dissension within the system without trying to destroy it.”

Wexler said he secretly became a Communist at the age of 19, while serving with the U.S. merchant marine during World War II. He did it, he said, because at the time he perceived the Communist movement as “the only party — the best and strongest people” to standup for the likes of organized labor, and to oppose fascism and racism.

Wexler — who says he was wounded in the war and won enough medals to be “what I guess was called a hero” — nonetheless said he lost his U.S. passport for five years for belonging to the Communist Party. He has not been a member of the party since then, he said, and could never go back to it.

“I wasn’t your regular Communist,” Wexler said. “I got just too dogmatic for my feelings — I didn’t want people to tell me what the party line was. When they stopped being what I thought was democratically operated, I said to myself that it wasn’t for me.

“I personally like to think of myself mostly as a person concerned with humanity, with life and survival. I guess I’m a bit unusual. I have my point of view, and I have close friends who share it — like Jane — and those who don’t.

“John Wayne and I were terrific friends, yet I disagreed with him specifically on many political views. I am absolutely convinced that he was a man who would never, intentionally, do anything to hurt other people. By the way, I was his last director — I never worked with him in a feature film, but I shot the TV commercials he did for Great Western Savings and Loan.”

Wexler said he filmed other commercials as well, for Miller beer, Wells Fargo Bank, United Airlines, Pepsi and Datsun, among others.

He has also, meanwhile, done anti-nuclear documentaries (“War Without Winners” and “No Nukes”) and another opposing the neutron bomb (“Wolf’s Head Test”).

Recently, he photographed the motion picture, “Ricard Pryor Live on the Sunset Strip” — the comedian’s first performance before a large public gathering since the burning incident in June 1980 that left him critically injured.

“Richard and I have never worked together before, but he’s a friend — and a national phenomenon,” Wexler said. “We filmed the movie with multiple cameras over two shows, but the first show was what we at first thought was going to be a disaster. He had a problem doing the jokes and he apologized and it was very moving, but I remember standing there thinking it was going to be a catastrophe. The second show, he was just great.”

Wexler said he soon hopes to direct and photograph a film, “Bernardo,” based on a script he wrote about a political kidnapping in Central America, with George Lucas (for whom he worked on “American Graffiti”) as producer.

It would mark Wexler’s only feature directing assignment since the 1969 movie, “Medium Cool,” an extremely realistic film about a TV cameraman which made use of actual shots of the actors at the 1968 Democratic convention, as well as the riots that followed.

“I want to direct more,” Wexler said. “It’s tough for cinematographers to pick projects to work on that aren’t his.”