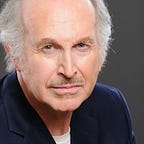

CONVERSATION WITH JACKIE COOPER: The Glamour — and Pain — of Hollywood’s Golden Age

(First published in August 1985. Jackie Cooper died of natural causes at the age of 88 on May 3, 2011, in Santa Monica, California.)

By Gregory N. Joseph

SKIPPY — “America’s boy,” Wallace Beery’s “Champ” sidekick, the quintessential pug-nosed, firm-chinned Anglo-Saxon kid of the 1920s and ’30s — will turn 63 on Sept. 15.

The key to his survival, Jackie Cooper was saying in an interview at the Del Mar Race Track one morning this week, was his marriage 31 years ago to the former Barbara Kraus, the mother of three of his four grown children.

If it hadn’t been for Barbara, Cooper explained, he might have succumbed to “booze or drugs” or a fatal spinout on some distant racing oval, all in search of himself.

Instead, he said, he matured when he married her (a middle-aged fling achingly recounted in his 1981 book “The Autobiography of Jackie Cooper: Please Don’t Shoot My Dog,” with Dick Kleiner, notwithstanding).

“She looks after me,” he noted without elaboration, at one point excusing himself to use a pay phone to call her “and let her know that I’m all right.”

He and his wife, who have abandoned their Beverly Hills domicile for the fourth consecutive summer to attend the races here, are renting a house in Solana Beach.

The Coopers own four horses. Pussycat is the only one running here (she was to run in the third race today) because the other three animals are injured. Cooper refused to get rid of them — which he contends many “horse people” would do — because , he says, that reminds him too much of Hollywood.

Cooper, who raised thoroughbreds and rode them in rodeo shows in his younger days, has always been a $20 horse player. He attended the opening of Del Mar in 1937, on hand because of his “acquaintanceship” (and not much more, he makes clear) with Bing Crosby, whose first wife, Dixie Lee, was a close friend of Cooper’s mother, Mabel, and lived with them for a while.

He loves horses for the same reason he does not enjoy directing child actors. He feels he was discarded, “used up,” in his early career, and cannot stand the thought of doing that to any living being.

“Like many of these horses, “ he said, his voice rising, “you use ’em up and use ’em up and they get a little lame, and you have people who want to get rid of them. That’s why I would never have a large stable of horses. I care too much individually about the animals.

“Barbara and I made sure that these two horses we had went to the kind of people who would care for them. Not just feed them and pet ’em … People just get rid of horses, that’s all. They don’t care what happens to them. They send them to Caliente, and if they break down and die on the track, they die on the track.

“You know, all actors are a hunk of meat to management. It’s a business. They can’t get attached to you and worry about you and how you’re going to grow up. And when you’re no longer of any use, you gotta be dropped. If you’re of no use to MGM or Paramount or United Artists or Warner Brothers or anybody else, you’re dropped. So, unless that child has some kind of schooling, where he or she has learned to earn a living doing something else, in almost every instance, that kid is not prepared to go out and take care of himself in the world …

“I just had to (keep acting) — I didn’t know how to do anything else. The best thing that happened to me was when Julie (the nickname for the late actor John Garfield) and another friend talked me into getting the hell out of California and learning my craft … I had to make my own opportunity — I put money in the first play I worked in, or I wouldn’t have gotten the role.

“I put money in a play I knew would be a failure, but I knew I would get reviews. And I knew if I got reviews, I could get other roles.”

Jackie Cooper …

To one generation, a perennial Our Gang favorite, eternally the precocious star of “The Bowery,” “Treasure Island,” and other pictures. To another, forever the homogenized leading man of the “The People’s Choice” and “Hennesey” television series of the 1950s and ’60s. And to the latest, the prolific Emmy-winning TV director (of movies like the upcoming “Izzy and Moe,” with Jackie Gleason and Art Carney) and occasional supporting actor (most recently as newspaper editor Perry White in the three “Superman” movies).

But there was always more, much more, to him than the public ever knew or could possibly comprehend given the mores of the times, this tormented man-child who was earning $1,300 a week by the time he was 9 years old in 1931— the same year he made “Skippy,” which brought him an Academy Award nomination as Best Actor at a record-setting, unbelievably young age and made him a star — but who didn’t learn to catch a ball until he was 25.

As his autobiography recounts, by the time he was 13, he was frequently having sex before 9 in the morning with the 20-year-old girl across the street. When he was 17, he was Joan Crawford’s lover. By the time he was 31, he was twice-divorced and a Hollywood has-been.

He tried to change, to grow. Acting in plays like “Mr. Roberts” (with Tyrone Power and John Forsythe), climbing through the Navy ranks (he retired two years ago as a captain in the reserves) and becoming a TV mogul (he headed Screen Gems for four years) helped.

The child is still in Cooper’s square face, a lost Skippy that never took time out to be a child but somehow leaped ahead to manhood.

At the moment, his attire — canary-yellow Western shirt, faded jeans, cowboy hat and boots — renders the still-compact Cooper indistinguishable from many others gathered in the threadbare owners and trainers restaurant near the race track’s stable area.

There, and when he is with his beloved filly in the stables, the Los Angeles-born Cooper’s speech slows into a subtle drawl. He has become one of the wranglers. A textbook survivor, he has spent a lifetime learning to fit in.

If Cooper is bitter, there is a reason.

His father went out to buy cigarettes when Jackie was 2 and never came back. His sickly mother, who was loving and supportive, died of cancer in November 1941. It was his pitiless grandmother who pinched and slapped him through the studio gates, where — together — they might earn $2 and a box lunch for a day’s worth of extra work.

He was cast in “Skippy” by his uncle, director Norman Taurog (who won an Academy Award for directing the film). The title of Cooper’s biography — “Please Don’t Shoot My Dog” — comes from a particularly upsetting, and revealing, episode that occurred during the making of that picture.

To induce the young Cooper to cry for a scene, his grandmother and Taurog pretended to have Cooper’s pet dog dragged off the set and “shot” by a security guard. They got their scene, and the youngster got back his dog in good condition— but the damage to Cooper had been done. He remained hysterical to the point that a doctor had to administer a sedative to him later that day.

The film was highly successful (it was nominated for an Academy Award as Best Picture) and spawned a sequel, “Sooky,” that was released the same year. Taurog also directed that — and Cooper once again starred.

It should not be surprising then that Cooper — to his way of thinking, the used and “discarded“ Cooper — grew up to become someone who would march to his own drummer and not hesitate to push back if he sensed he was being disrespected.

In his book, for example, Cooper, who directed much of the first season and a half of the hit comedy series “M*A*S*H,” is highly critical of its star, Alan Alda, whom he depicts as cool, aloof and jealous of the power Cooper wielded on the set.

“I’ve buried the hatchet with Alan since the book,” Cooper said during the interview. “He ran into me at Fox and said he was so sorry, he never knew I felt that way, he was sorry if he ever hurt me. Then he stuck out his hand and we shook. It’s hard to stay upset with a fellow who does that.”

Ditto Jack Klugman, who is appearing this month in “Tribute” at the Lawrence Welk Village Theater. Cooper describes working with Klugman on his TV series, “Quincy,” and how Klugman said Cooper would direct as many more episodes as he wanted. Cooper writes that he went off to work on “Superman,” and when he got back, “I’ve never heard from Jack Klugman again regarding ‘Quincy’ to this day.”

Cooper said during the interview that he ran into Klugman “the other day” and “we got along fine.”

He offered a few other assessments of famous people he has known:

— Bing Crosby: “I think, just judging from Bing’s kids, the kids he had with Dixie, and his almost totally ignoring them at a certain age, people that I’ve known that have known Bing over a number of years say that his excuse was that he was disappointed in them. Well, that’s not an excuse for a father, to me — there is no excuse for that.

“He used to come around our house in the 1930s, when he was singing with Paul Whiteman. He met Dixie through my mother. I don’t know what influenced him, but I do know those of us, as you get older, your deportment is really the result of your training or environment … I don’t know what happened to Bing in those years. I mean, you read about all the happy things of his singing in college and so forth, but when you speak to a lot of people, honest people, who worked with Crosby, he did not have a lot of friends …

“In later years, I wouldn’t see him for three, four, five years — as a teenager, I’d have some flare-up of notoriety and be invited on his radio show, and I wouldn’t be invited into his dressing room for a Coke.”

— Wallace Beery: “Nobody really knew Wally. I was an affectionate kid, he was always playing my father. I had no father, and I was always falling in love with whoever was playing my father … I mean, I’d cry when the picture was over, I didn’t want to stop seeing those people every day.

“But Wally shunned any affection. Evidently, he was concerned with being upstaged. Being small, he could handle me. He’d turn me as we were talking and put my back to the camera and he could get his face on the camera. Before the first picture of four with him — ‘The Champ’ — was over, having felt rejected by him, I didn’t want to be around him. It was difficult to make the other pictures with him. It took a lot of talk by my mother.”

Cooper also recalled Clark Gable as “a beautiful guy” whose political and religious philosophies leaned to the right; Robert Taylor as “masculine,” “a fine horseman” and “like an older brother to me,” and Bette Davis as “terrific, always on time and very directable.”

Now it was time to go tend his horse. Cooper rose, shook hands — a handshake one interviewer called “almost painful” — and mentioned his next film project.

“It’s the story of a former child actress,” he said. “I guess I can’t get the subject off my mind.”