CONVERSATION WITH JANET LEIGH: On the Difference Between Working for Welles and Hitchcock. And Not Blinking in the ‘Psycho’ Shower.

“To me, ‘Psycho’ was a big comedy. Had to be.” — Alfred Hitchcock

“I don’t believe in learning from other peoples’ pictures. I think you should learn from your own interior vision of things and discover, as I say, innocently, as though there had never been anybody.” — Orson Welles

By Gregory N. Joseph

JANET LEIGH worked for two of the most legendary directors in the history of film : Alfred Hitchcock and Orson Welles. Two acknowledged masters of the cinematic art whose influence is still being felt, discussed and debated to this day, they differed greatly in everything from style to approach. To say that their movies will never be confused is a vast understatement. It doesn’t take a film scholar to see the obvious and very palpable difference in what they present on screen the moment the lights dim and the curtain goes up.

But it doesn’t end there.

Welles was famously outspoken in his critcism of a whole range of directors and various film figures, from Charlie Chaplin to Laurence Olivier to Woody Allen. But he saved his harshest invective for Hitchcock: “I’ve never understood the cult of Hitchcock. Particularly the late American movies. Egotism and laziness. And they’re all lit like television shows … I saw one of the worst movies I’ve ever seen the other night (Hitchcock’s ‘Rear Window’) … Complete insensitivity to what a story about voyeurism could be.”

Leigh is perhaps unique among actors of her generation because she had the opportunity to work for both Hitchcock and Welles.

And she had an expansive enough career (in many regards, breathtakingly so) to be able to understand, and carry out, the very different and difficult demands of each.

Born Jeanette Helen Morrison on July 6, 1927 — an actress, singer, dancer, and later author, known professsionally as Janet Leigh — she was raised in Stockton, Calif., by working-class parents and discovered at the age of 18 by Oscar-winning Golden Age actress Norma Shearer, who had been married to the legendary boy-wonder “last tycoon” producer Irving Thalberg at the time of his untimely death, and helped Leigh win a contract at his former studio, MGM.

By any yardstick, Leigh appeared in an eclectic group of films that underscored an unusually impressive acting range, from “Little Women” (1949), “Scaramouche” (1952), “The Naked Spur” (1953) and “The Manchurian Candidate” (1962) to “Bye Bye Birdie” (1963).

But it was her work for Hitchcock, especially, that drew notice, specifically in his 1960 film, “Psycho,” which turned out not only to be his most successful at the box office, but a cinematic benchmark defining an era and its evolving culture, and the standard against which thrillers are still measured.

For Leigh, it was the high-water mark of her acting career. She won a Golden Globe as Best Supporting Actress and was nominated for an Academy Award in the same category for her performance in the film, with the scene in which her character is bludgeoned to death in the shower becoming one of the most famous — and analyzed — in motion picture history. The film represented a seismic turning point in the horror genre.

“Psycho,” described as “a psychological horror thriller,” has a screenplay written by Joseph Stefano based on the novel of the same name by Robert Bloch, and follows the path of fleeing embezzler Marion Crane (Leigh) who encounters depraved motel proprieter Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins, in his career-defining role), with a detective, Marion’s lover, and her sister subsequently investigating her disappearance.

In 1992, the Library of Congress designated it as “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant” in choosing it for preservation in the U.S. National Film Registry.

In 2022, Variety ranked it as the greatest film ever made, stating, “There’s hardly a frame of Alfred Hitchcock’s cataclysmic slasher masterpiece that isn’t iconic. If you don’t believe us, consider the following: Eyes. Holes. Birds. Drains. Windshield wipers. A shower. A torso. A knife. ‘Blood, blood!’ A Victorian stairway. Mother in her rocking chair. For decades, ‘Psycho’ enjoyed such a cosmic pop-cultural infamy that, in a funny way, its status as a work of art got overshadowed. Hailing it as Hitchcock’s greatest movie — let alone the greatest movie ever made — wouldn’t have seemed quite respectable. Yet there’s a reason that every moment in ‘Psycho’ is iconic, and that Anthony Perkins and Janet Leigh, as Norman Bates and Marion Crane, became fixed in our imaginations like figures out of a dream …”

“Touch of Evil,” a 1958 film noir written and directed by Welles with a screenplay loosely based on Whit Masterson’s novel “Badge of Evil,” centers on a murder investigation on the U.S.-Mexican border involving a Mexican special prosecutor (Charlton Heston) on his honeymoon with his American wife (Leigh). They encounter a corpulent, recovered-alcoholic veteran police captain (Welles) with a penchant for bending the rules and a gaggle of suspicious, dangerous characters as they try to untangle who placed a time bomb inside a vehicle killing a man and his stripper girlfriend.

In post-production, Welles and Universal Pictures officials had creative differences about the film, and Welles was forced out, with Universal-International incorporating editing revisions that changed its construction considerably, making it more conventional, even requiring some re-shoots (which Heston in particular disliked and resisted out of respect for Welles). Welles responded to the editing by writing a 58-page memo explaining his creative intent and asking that the film be restored accordingly, which eventually it was, in 1998, years after his death in 1985 at the age of 70. Although not a true “director’s cut,” the re-edited version was hailed and received awards from the New York Film Critics Circle, the Los Angeles Film Critics Association and the National Society of Film Critics.

The picture in its initial form, panned by many critics, nonetheless was embraced by European audiences and won top prizes at the 1958 Brussels World Film Festival. Its reputation began growing in the 1970s and now the film is looked upon not only as one of Welles’ finest screen efforts but one of the best noir films of the classic era. In 1993, it also was selected for preservation by the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress.

Leigh, in a 1984 interview during which she was publicizing her autobiography, “There Really Was a Hollywood,” used her experience filming “Psycho” to draw a distinction between the two legendary directors.

As she explained, they couldn’t have been more different.

“Welles was very impromptu — like he would be doing an improvisation,” she said. “He’d go and see something and say, ‘Oh, I love that shot — let’s use it,’ and change the shot so he could utilize the clouds or whatever it was he saw.

“Whereas with Mr. Hitchcock (who died in 1980 at the age of 80), everything was absolutely delineated before the picture ever started. He had Saul Bass — who did the title design for ‘Psycho’ and ‘Man with the Golden Arm’ — do a storyboard for every single angle in the shower scene. Saul did the montage on the storyboard and that was all set before the picture ever started. There was no deviation from that whatsoever.”

(Donald Spoto, in his book, “The Dark Side of Genius: The Life of Alfred Hitchcock,” maintains that Hitckcock made two additions to the “Psycho” story board: of a knife entering the woman’s abdomen — actually a fast-motion reverse shot — and blood and water running down the shower drain.)

Leigh insisted that working for Hitchcock — who once famously said, “I never said actors are cattle; what I said was all actors should be treated like cattle” — was a surprisingly relaxing experience. (Cary Grant, who starred in four films directed by Hitchcock — “Suspicion,” “Notorious,” “To Catch a Thief” and “North by Northwest” — was similarly smitten with the director, saying he “whistled on the way to work” because Hitchcock’s productions were so professional and well-planned: “I have only happy memories. They’re all vivid because they’re all interesting. It was a great joy to work with Hitch. He was an extraordinary man.” The feeling was mutual. Hitchcock called Grant “the only actor I ever loved in my entire life.”)

Leigh recalled that Hitchcock told her he would not give her direction during filming unless she was trying to take more than her share of “the acting pie” or not enough, or if she was “having trouble motivating the necessary timed motion.”

She said that her most difficult moment in the film was for a scene that went on to become part of cinema history, a long closeup of her open “dead” eye in the “Psycho” shower. The flesh-colored moleskin she was wearing over her breasts came off in the steam of the hot water.

“It was out of view of the camera, but maybe not of everyone else, so I had a decision to make,” she said. “Did I spoil the difficult shot and move and be modest, or did I hold still? I decided not to spoil the shot.”

Leigh said she received the best acting advice she ever got from co-star Van Johnson in her very first film, 1947’s “The Romance of Rosy Ridge.”

“In one scene, I got between him and the camera, and clocked him,” she recounted with a shudder. “They (yelled) cut and I felt so badly. Van took me aside and said, ‘Don’t worry about where the camera is, don’t worry about where the lights are. The camera will find you.’

“In other words, if you start thinking about which lights are right or where the camera is, if you start thinking about all of that, you can’t concentrate on what you’re saying. To this day, I can’t tell you what a key light is.”

The actress passed away at age 77 on Oct. 4, 2004.

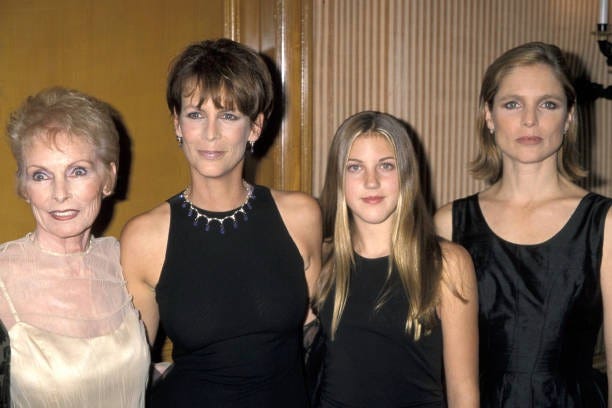

Nearly two decades later, in 2023, actress Jamie Lee Curtis, Leigh’s daughter by her one-time husband, the 1950s screen heartthrob Tony Curtis, won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress for her performance in the Best Picture-winning film “Everything Everywhere All At Once.”

Jamie Lee, in her passionate and animated acceptance speech, mentioned that many years before, both of her parents had been movie stars and were nominated for Oscars themselves.

It was a moment that would have prompted Janet Leigh, had she still been around, to admit that there really was a Hollywood — still.