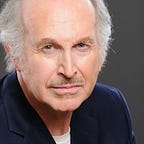

CONVERSATION WITH ‘AGONY AND ECSTASY’ AUTHOR IRVING STONE: Making History Personal

“My goal always is to tell a universal story, meaning it’s about a person who has an idea, a vision, a dream, an ambition to make the world somewhat less chaotic.” — Irving Stone

By Gregory N. Joseph

AUTHOR IRVING STONE’S biographical novels bringing seminal figures to life have become part of our culture, two of his most popular works being “Lust for Life,” the book about the troubled Dutch artist Vincent van Gogh that launched Stone’s career, and “The Agony and the Ecstasy,” which focused on the conflict between Michelangelo and Pope Julius II during the painting of the Sistine Chapel’s ceiling.

When I met Stone in 1971 at his fashionable home that was balanced on white stilts high on a ledge overlooking the rolling slopes of Beverly Hills, he was an elegant, forthcoming and focused interview subject, sensing as only another writer can my unease as I grappled with how to string together meaningful questions that somehow would result in a profile that accurately depicted the man sitting in front of me while doing justice to his estimable literary achievements.

My meeting with Stone was timed to coincide with the relase of his latest book, the historical novel “The Passions of the Mind” about Sigmund Freud, the Austrian neurologist and founder of psychoanalysis.

Indeed, profiling authors can be a daunting task, and interviewing one internationally famous for his attention to detail and meticulous research was even more challenging.

Few were more attuned to detail than Stone.

According to his afterword for “Lust for Life,” he used Van Gogh’s letters to his brother Theo for his book, and did much of his research in the field, a practice he often followed, as when he spent many years living in Italy while working on the Michelangelo tome (the Italian government lauded Stone with several honorary awards during this period for his cultural achievements highlighting Italian history).

Stone’s fastidious research of Van Gogh for “Lust for Life” included correspondence with Dr. Felix Rey, the physician who had treated the artist after he cut off his own ear. Rey had been the subject of one of Van Gogh’s paintings and became Stone’s friend.

Although best known for his novels, Stone also wrote a number of nonfiction books, such as his biography of Clarence Darrow, “Clarence Darrow For the Defense,” about the attorney known both for his defense of thrill killers Leopold and Loeb and for his defense of John T. Scopes in the 1925 “Monkey Trial,” which centered on a biology teacher who taught about evolution in Tennessee.

Stone also wrote a biography about Earl Warren, who had been a California governor, running mate of presidential candidate Thomas E. Dewey in his famous upset loss to Harry S. Truman in 1948, and later a controversial Supreme Court Chief Justice appointed by President Dwight Eisenhower who presided over a series of landmark decisions.

As a young reporter, I struggled greatly to pose just the right questions of Stone as I sought not only to discuss his newest book, but to explore his personality and what motivated him to become a writer in the first place.

Stone sensed my nervousness, and instantly put me at ease by noting that I was about the same age as his son.

Then, as if to tell me never to give up in my dreams and pursuit of writing, he turned and pointed to a nearby room with a large bookshelf filled with dozens of copies of “Lust for Life.” They were copies of the book published in nearly every language imaginable. It was breathtaking.

Incredibly, Stone explained that the book had been rejected by 17 publishers over three years before it was published in 1934.

As if that weren’t discouraging enough, he recounted how a close friend — the great writer William Saroyan — had refused to read his manuscript at all.

Saroyan was an Armenian-American novelist, playwright, and short story writer who went on to win the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 1940, and in 1943, won the Academy Award for Best Story for the film adaptation of his novel, “The Human Comedy.”

When Stone and Saroyan were beginning their writing careers, they lived near each other and got together to play cards every week.

At one point, Stone suggested that he and Saroyan exchange their latest works and give their opinions to each other the following week. The first manuscript Stone gave to Saroyan was “Lust for Life.”

When the time came to get together the following week, Stone eagerly offered his very positive opinion about Saroyan’s work, and waited for his friend’s assessment of his effort. But Saroyan said he hadn’t read Stone’s work— and never would, noting, “I want what I write to be pure Saroyan.”

Stone was crushed. As he recalled the story to me, it was clear the pain of being rejected by a friend and fellow writer was still fresh all these years later, and apparently, he was determined not to do the same thing with other writers. Including me.

As I turned to leave our interview, he surprised me with a copy of “The Passions of the Mind,” which he insisted upon signing. His inscription read: “With warmest regards to a fellow writer— Irving Stone.”

Stone, who was born Irving Tennenbaum on July 14, 1903 (he legally changed his last name to “Stone,” that of his stepfather, after his mother remarried), died on Aug. 26, 1989.

I still have that signed copy of “The Passions of the Mind,” and regard it as a treasure. Stone’s thoughtful gesture and encouragement after describing his own travails has sustained me more times than I care to admit.

Once again, Irving Stone had succeeded in making history movingly personal — this time, his own, for me. For that, I remain eternally grateful.