CONVERSATION WITH ROD STEIGER: The Bumpy Backstage Odyssey of Film’s Most Famous Taxi Ride

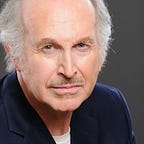

(When I profiled Rod Steiger in 1989 in conjunction with a TV movie he had made, he was as outspoken — and as fascinatingly complex — as his screen persona. He disclosed, among other things, that “the worst career mistake I ever made” was in turning down the starring role in “Patton,” a part ultimately taken by George C. Scott that won him the Oscar, even though Scott famously rejected the award. When I mentioned the difficulty that Steiger might have faced in winning a second Academy Award so close to his first for “In the Heat of the Night,” he shot back in his famous, patented clipped delivery, “Listen! Coulda happened!” Which led me to inquire why he had turned down the TV version of “Heat.” “Too late, too late,” he said. As for the Oscar and what it had done for his career, he noted: “You win an Oscar on Friday and they forget about you by Monday.” He was an excellent interview, a fighter, someone who had been through the Hollywood wars and wasn’t afraid to speak his mind. He didn’t hold back in discussing his experiences in “On the Waterfront,” and in particular working with Marlon Brando. Steiger died in 2002 at the age of 77, and Brando died in 2004 at 80.)

“I didn’t have to do any directing there. The cab scene was written so well and [Brando and Steiger] understood it.” — Elia Kazan, director, “On the Waterfront”

“When you see Brando in the famous cab scene in ‘On the Waterfront,’ it’s still breathtaking.” — Anthony Hopkins

“‘On the Waterfront’ came out and there were 150 guys [at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts] all doing Brando impressions.” — Albert Finney

“When I first saw ‘On the Waterfront,’ I couldn’t move. I couldn’t leave the theatre. I’d never seen the like of it.” — Al Pacino

“I think there’s a well-known contest in the acting profession to see who can say the best stuff about Marlon — Jack Nicholson

By Gregory N. Joseph

MARLON BRANDO’S PERFORMANCE as washed-up boxer Terry Malloy in Elia Kazan’s stunning Oscar-winning 1954 film “On the Waterfront” helped establish him as arguably the leading actor of his generation, whose approach and style are still influencing actors to this day.

Produced by Sam Spiegel, “On the Waterfront” was directed by Kazan from a script by Budd Schulberg with a musical score composed by Leonard Bernstein (his only original film score not adapted from a stage production).

The story, inspired by Malcolm Johnson’s Pulitzer Prize-winning series of articles “Crime on the Waterfront” in The New York Sun, focused on union violence and corruption among longshoremen and starred Brando, Karl Malden, Lee J. Cobb, Rod Steiger and Eva Marie Saint (in her film debut).

An across-the-board success, it brought an even dozen Academy Award nominations, winning eight, including Best Picture, Best Director for Kazan, Best Actor for Brando, and Best Supporting Actress for Saint. Steiger, Malden and Cobb were all nominated for Best Supporting Actor.

In 1997, the American Film Institute named it the eighth-greatest American movie of all time (10 years later, AFI ranked it 19th). In 1989, the film became one of the first 25 films to be christened “culturally, historically or aesthetically significant” by the Library of Congress and chosen for preservation by the National Film Registry. In 2022, Variety ranked it as the 36th greatest movie of all time.

The signature moment in the movie, one that drives home Brando’s uniqueness, is his famous “I coulda been a contenda” scene with Steiger, who plays the boxer’s racketeering (and doomed) brother Charley, who has sold his haunted, beat-up sibling down the river:

Charley Malloy: Look, kid, I — how much you weigh, Slick? When you weighed one hundred and sixty-eight pounds you were beautiful. You coulda been another Billy Conn, and that skunk we got you for a manager, he brought you along too fast.

Terry Malloy: It wasn’t him, Charley, it was you. Remember that night in the Garden you came down to my dressing room and you said, “Kid, this ain’t your night. We’re going for the price on Wilson.” You remember that? “This ain’t your night”! My night! I coulda taken Wilson apart! So what happens? He gets the title shot outdoors on the ballpark and what do I get? A one-way ticket to Palooka-ville! You was my brother, Charley, you shoulda looked out for me a little bit. You shoulda taken care of me just a little bit so I wouldn’t have to take them dives for the short-end money.

Charley Malloy: Oh I had some bets down for you. You saw some money.

Terry Malloy: You don’t understand. I coulda had class. I coulda been a contender. I coulda been somebody, instead of a bum, which is what I am, let’s face it. It was you, Charley.

What audiences didn’t realize when the film debuted was that there were simmering tensions behind that particular scene and the movie as a whole, which may, in retrospect, have injected an unplanned jolt of energy that made the picture even greater than the sum of its quite impressive parts.

During a long interview recapitulating his career, Steiger, who acknowledged that “Waterfront” put him on the cinematic map, said of this exchange, the film’s most memorable scene and one of the most famous in all of motion picture history: “At the time, Brando was the toast of the town, Broadway and Hollywood. When we filmed the backseat scene, we filmed it the usual way, the master shot of us both, again with a close-up on Brando and then with my close-up.

“I stayed to deliver my lines from off-camera to Brando when he did his close-ups, but when it came time for my close-up, Mr. Brando left, walked away.

“I was doing my lines with the script girl, who was reading his lines off-camera.”

Steiger explained that what made shooting the scene even more complex than it should have been was that it was shot in a small studio, what amounted to a long narrow room (“If we put our arms out the window we would have hit a wall”), and that there were no special effects spliced in to give it an aura of realism, footage of actual streets projected behind and on the sides of the characters.

Kazan, who was furious with Siegel for not seeing to this, was fretting what to do until someone mentioned having seen a cab earlier in the day with Venetian blinds mounted across the back window. Voila. Several hours later, the scene could be filmed.

But with a different approach: Kazan would have to focus his camera close-up on Brando and Steiger. Suddenly it had become an intense character study. (Nehemiah Persoff, who portrayed the cab driver in the scene, said he was perched on a wooden box instead of a car seat and that Kazan leaned in and told him that for his close-up he should play his character as though Charley had killed his mother.)

Brando later expressed reservations about the scene:

“A movie that I was in, called ‘On the Waterfront,’ there was a scene in a taxicab, where I turn to my brother, who’s come to turn me over to the gangsters, and I lament to him that he never looked after me, he never gave me a chance, that I could have been a contender, I coulda been somebody, instead of a bum … ‘You should of looked out after me, Charley.’ It was very moving. And people often spoke about that, ‘Oh, my God, what a wonderful scene, Marlon, blah blah blah blah blah.’

“It wasn’t wonderful at all. The situation was wonderful. Everybody feels like he could have been a contender, he could have been somebody, everybody feels as though he’s partly bum, some part of him. He is not fulfilled and he could have done better, he could have been better. Everybody feels a sense of loss about something.

“So that was what touched people. It wasn’t the scene itself. There are other scenes where you’ll find actors being expert, but since the audience can’t clearly identify with them, they just pass unnoticed. Wonderful scenes never get mentioned, only those scenes that affect people.”

In a profile of Brando by Truman Capote published in New Yorker magazine on Nov. 9, 1957, “The Duke in His Domain,” the actor is quoted as being less than enamored of the way the encounter was presented, Steiger’s performance in it, and, for that matter, the movie itself:

“That was a seven-take scene, and I didn’t like the way it was written. Lot of dissension going on there.

“I was fed up with the whole picture. All the location stuff was in New Jersey, and it was the dead of winter _ the cold, Christ! And I was having problems at the time. Woman trouble.

“That scene. Let me see. There were seven takes because Steiger couldn’t stop crying. He’s one of those actors who loves to cry. We kept doing it over and over. But I can’t remember just when, how it crystallized itself for me.

“The first time I saw ‘Waterfront,’ in a projection room with Gadge (director Elia Kazan), I thought it was so terrible I walked out without even speaking to him.”

It is interesting to note that Brando almost didn’t do “On the Waterfront” at all.

According to Paul Newman’s memoir “The Extraordinary Life of an Ordinary Man,” published posthumously in 2022 fourteen years after Newman’s death, Brando initially didn’t want to work for Kazan, and Newman was considered the next-best choice as his replacement, to the point of beginning rehearsals.

This was during the height of McCarthyism, and Kazan had been called to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee [HUAC]. Instead of risking his career by refusing to testify or condemning the committee’s actions altogether as many in the industry had courageously done to the detriment of their livelihoods, personal lives and sometimes their health, Kazan chose to go before the committee and name names. Many in Hollywood never forgave him for it, so much so that years later when he was presented an Honorary Oscar, some in the audience refused to applaud or stand.

This put Brando off and he considered Kazan a “squealer,” according to fellow “Waterfront” cast member Karl Malden, but he ultimately relented and agreed to appear in the film.

Brando’s “misgivings” notwithstanding, the picture was hugely successful with the masses but also managed to make a highly charged political statement that reflected the McCarthy period during which it was filmed.

Steiger recalled that political differences often boiled to the surface behind the scenes. When fellow cast member Cobb, who played a vicious, crooked union boss in the film, invited Steiger to his nearby apartment for lunch one day during the shoot, it was uneventful — but not in a good way.

Their political views, it so happened, were diametrically opposed.

“I sat there just listening, chewing and staring at the knot in his tie,” remembered Steiger.

Steiger was no stranger to sharing the screen, and holding his own, with film legends. He played a fight promotor opposite Humphrey Bogart in Bogie’s last film, “The Harder They Fall,” a 1956 film noir about corruption in professional boxing, and appeared alongside groundbreaking actor Sidney Poitier in the 1967 civil rights drama “In the Heat of the Night,” a Best Picture winner that finally brought him his own Academy Award for Best Actor for his kinetic performance as a bare-knuckles-tough, gum-chewing Southern police chief.

But it was “On the Waterfront” — and that backseat scene with Brando — that, fairly or not, defined Steiger’s career and cemented his place in movie history in a never-to-be-forgotten ride for the cinematic ages.